Pathological Demand Avoidance (PDA): The Invisible Battle for Autonomy in a World of Expectations

When Doing “Nothing” Is a Nervous System Response

For many people, functioning in the world means finding a balance between internal desires and external expectations. But for individuals with Pathological Demand Avoidance (PDA), that balance can feel impossible. The more they want—or are expected—to do something, the more their body and brain resist.

This isn’t procrastination or rebellion. It’s the lived experience of a nervous system in a constant state of defense, doing everything it can to avoid perceived threats—even when those “threats” come in the form of everyday requests, responsibilities, or personal goals.

And often, it goes completely unnoticed by others.

PDA is most commonly associated with autism, but it can also be present in individuals with ADHD, trauma histories, and other forms of neurodivergence. While not a standalone diagnosis, it is increasingly recognized as a distinct profile requiring specific, relational, and non-pathologizing forms of support.

What Is Pathological Demand Avoidance?

Pathological Demand Avoidance is a profile marked by an intense, persistent, and involuntary resistance to everyday demands, regardless of how seemingly minor or self-generated they are. This resistance is often rooted in anxiety and a protective need to preserve autonomy, predictability, and emotional safety.

What makes PDA distinct is that it’s not simply a behavioral issue—it’s a physiological and emotional defense mechanism. The individual’s system perceives demands as a threat to control or selfhood, and responds with avoidance, withdrawal, masking, or shutdown.

These demands might include:

Getting out of bed and showering

Responding to a text

Attending a work meeting

Following through on a personal goal

Even making a therapy appointment

When demands—internal or external—feel like intrusions, they can trigger the body’s fight, flight, freeze, or fawn response, even if the person deeply wants to do the thing.

PDA Can Show Up As…

Because Pathological Demand Avoidance isn’t always loud or disruptive, it can show up in subtle, everyday ways—often masked as perfectionism, procrastination, executive dysfunction, or even social anxiety. Here are a range of real-life examples, from internalized to overt, to help illustrate how PDA might look in different people:

Mild or Internalized Examples:

Overthinking simple tasks. You want to reply to a message from a friend but you’ve reread it five times, can’t find the “right” tone, and now two weeks have passed.

Sudden avoidance of plans you made and were excited for. You’ve looked forward to dinner with a friend all week—but as the time approaches, you feel irritable, panicked, and tempted to cancel last-minute.

Perfectionism masking avoidance. You want to submit a job application but spend days tweaking your resume, rereading the listing, or avoiding it altogether because you can’t get it “just right.”

Mental “freezing” over self-care. You know you need to shower, eat, or take your medication—but feel physically stuck, like your body refuses to cooperate even as your brain urges you to act.

Moderate or Relationally Impactful Examples:

Agreeing to help someone, then avoiding them. You tell a colleague or family member “Sure, I can do that,” because it feels easier in the moment—but dread it so much you ignore reminders or messages and feel intense guilt.

Constantly renegotiating internal goals. You commit to a new habit, like going to the gym or journaling, but by day two it feels impossible. Even internally saying “I’ll do it every day” feels too rigid and triggering.

Feeling trapped by your own schedule. You carefully plan your week, but once it’s in your calendar, every item on the list feels suffocating—even if you made the schedule yourself.

Exhaustion from masking at work. You show up to meetings, deliver on tasks, and look like you’re managing—but spend evenings and weekends completely shut down, avoiding emails, texts, and decisions.

Severe or Functionally Disruptive Examples:

Meltdowns when pressured to complete tasks. A simple reminder from a partner (“Can you take out the trash?”) sparks a panic response, irritability, or a fight—not because you’re unwilling, but because you feel emotionally ambushed.

Avoiding therapy or help—even when it’s needed. You want support, but the idea of scheduling, committing to sessions, or following through on therapeutic “homework” feels like too much. You ghost, cancel, or disengage.

Feeling incapable of following through on any plan. Even things you’re passionate about—creative projects, relationships, personal goals—are abandoned when they start to feel like obligations.

Intense shame spirals. You struggle to explain to others—or yourself—why you can’t “just do it,” and carry heavy self-judgment, feeling like a failure, burden, or disappointment.

These behaviors are often misunderstood as laziness, avoidance, irresponsibility, or immaturity. But for someone with a PDA profile, they are protective responses to internal pressure and fear of losing autonomy.

If any of these examples resonate, you’re not alone—and you’re not broken. PDA isn’t about a lack of willpower. It’s about a nervous system that learned to protect itself through resistance.

The Hidden Nature of PDA: High Masking and Misunderstanding

Because PDA is often masked—especially in women, people-pleasers, and high-functioning individuals—it’s commonly misinterpreted or missed altogether. The person might appear engaged, responsible, or agreeable on the surface while privately experiencing deep overwhelm, anxiety, and collapse.

PDA can show up as:

Intense procrastination, even with tasks the person values

Panic or anger when asked to do something “now”

Sudden withdrawal from plans or social interactions

Meltdowns that seem to come “out of nowhere”

Saying yes—and then ghosting, cancelling, or avoiding follow-through

Chronic burnout despite being seen as high-achieving

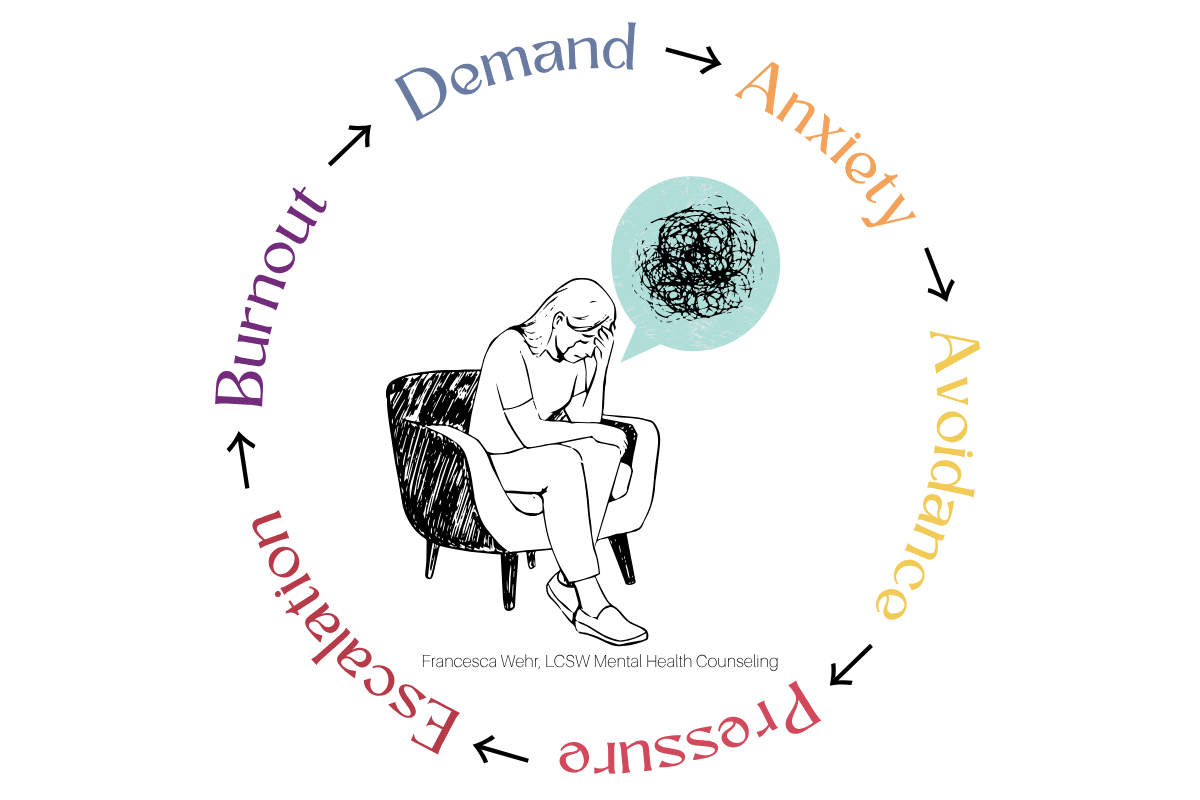

The Demand-Avoidance Cycle in Action

When Pathological Demand Avoidance (PDA) overlaps with anxiety, Rejection Sensitive Dysphoria (RSD), and trauma—as it often does—it tends to follow a recognizable emotional loop. This overlap is common because PDA frequently appears in neurodivergent individuals—particularly those with autism, ADHD, or sensory processing differences—who are more likely to carry histories of chronic stress, emotional invalidation, or developmental trauma. It’s also connected to the way neurodivergent brains process threat, autonomy, and emotional regulation; heightened sensitivity in the nervous system and differences in executive functioning, interoception, and social processing can make even minor demands feel overwhelming or unsafe.

The cycle often begins when a demand is introduced, either externally (a request, a task, a deadline) or internally (a goal, a to-do list, even a desire to connect). This triggers anxiety, which then leads to avoidance as a protective reflex. The more the demand is reinforced, repeated, or pressured—either by others or by the person’s own inner critic—the more the nervous system escalates into dysregulation, shutdown, or burnout.

This pattern can be deeply frustrating for the individual and confusing for those around them. But when viewed through a trauma-informed, neurodivergent-affirming lens, it becomes clear:

This isn’t a lack of motivation—it’s a nervous system trying to stay safe.

The cycle below illustrates this pattern:

PDA and Rejection Sensitive Dysphoria (RSD)

The cycle above illustrates how a simple demand can spiral into overwhelm when a person's nervous system interprets it as a threat. For many individuals with ADHD, trauma histories, or emotionally invalidating environments, Rejection Sensitive Dysphoria (RSD) adds another layer of complexity—amplifying the emotional intensity of the PDA response.

RSD is a heightened emotional sensitivity to perceived rejection, criticism, or failure. It can make the stakes of a basic request feel emotionally catastrophic. When RSD and PDA overlap, the internal script might sound like:

“If I try and fail, I’ll disappoint them.”

“If I say no, they’ll think I’m selfish.”

“If I can’t do it right, I’ll be rejected.”

“If I don’t respond soon enough, they’ll think I don’t care.”

“If I cancel again, no one will want to be close to me.”

This makes every decision feel emotionally loaded. The demand isn’t just “do the thing”—it’s “do it perfectly, on time, and without risking disconnection.” That emotional weight can be paralyzing, especially for a nervous system already in a chronic state of hypervigilance.

As a result, the person may become trapped in a self-perpetuating cycle:

Anticipating rejection or criticism

Avoiding the demand to escape that pain

Feeling intense shame for avoiding it

Withdrawing further out of self-protection

This cycle is exhausting and isolating. It also explains why PDA can look like social anxiety, executive dysfunction, or even personality disorder traits—when what’s really happening is a deep fear of rejection, failure, or unworthiness tied to perceived demands.

The Role of Trauma and Attachment

Pathological Demand Avoidance (PDA) and Rejection Sensitive Dysphoria (RSD) don’t emerge in a vacuum. In many individuals, especially those with histories of developmental, relational, or attachment trauma, these patterns are shaped by early environments where safety, love, or acceptance were conditional—offered only when the child performed, complied, or made themselves small.

In these cases, a demand isn’t just a task. It’s a potential reactivation of a relational wound. The nervous system remembers the emotional cost of getting it “wrong”—and responds accordingly.

This is particularly true for individuals who:

Were punished for asserting boundaries or expressing needs, learning that autonomy leads to rejection or retaliation.

Were parentified—expected to regulate their caregivers or take emotional responsibility for others before developing their own sense of self.

Grew up with emotionally inconsistent caregivers who responded to normal child behavior with anger, guilt-tripping, or withdrawal of affection.

Were praised only for achievement, obedience, or emotional suppression, and rarely seen or soothed when struggling or dysregulated.

Learned that love was earned, not freely given—and that safety came from compliance, not authenticity.

In these relational contexts, demands begin to feel like emotional traps:

If I say no, I might lose connection.

If I struggle, I’ll be shamed.

If I ask for help, I’ll be punished—or ignored.

Over time, the body internalizes this fear and begins to respond automatically. What looks like “resistance” is often a survival strategy hardwired into the nervous system.

The individual avoids demands because they associate them with criticism or collapse.

They disconnect to preserve themselves from the weight of expectation.

They shut down because the demand has become entangled with early experiences of powerlessness, fear, or abandonment.

This is why PDA cannot be addressed by enforcing compliance or increasing motivation. When the root is trauma, the path forward must be relational. The nervous system needs new experiences of safety, trust, and autonomy—where demands are not threats, and connection isn’t contingent on performance.

How to Support PDA (With or Without RSD)

Supporting someone with PDA means moving away from traditional behavioral approaches focused on compliance, productivity, or “fixing.” It means creating emotionally safe, autonomy-respecting relationships—at home, in therapy, and in daily life.

What Helps:

Collaborative language: Invite rather than instruct. “Would you be open to trying this together?”

Normalize agency: Affirm that the person has choice. “It’s okay if now isn’t the right time.”

Break down internalized shame: “Struggling doesn’t make you lazy—it means your nervous system needs support.”

Attend to RSD: Reassure them that setbacks or avoidance don’t affect your regard for them.

Structure with softness: Predictable frameworks (like check-ins, scaffolds, or flexible routines) can create safety without pressure.

Use co-regulation: Emotional safety comes before executive functioning. Meet dysregulation with calm presence, not instruction.

For therapists, this may mean:

Loosening expectations around homework, scheduling, or “progress”

Allowing greater autonomy in pacing and session focus

Watching for fawn responses that may mask the client’s overwhelm or avoidance

Explicitly addressing RSD and the client’s internal narratives of failure

Final Thoughts: Rewriting the Narrative

Pathological Demand Avoidance is not a refusal to participate in life—it’s a protective mechanism built by a system that has experienced pressure without safety, expectations without flexibility, and connection conditioned on performance.

When PDA is layered with Rejection Sensitive Dysphoria, the inner world becomes even more fraught. The person isn’t just avoiding tasks—they’re avoiding potential disconnection, shame, and loss of self-worth.

But there is a way forward.

The antidote is not more pressure. It’s not more structure or willpower or discipline.

The antidote is relational safety. Emotional permission. Regulation. Compassion.

Only when the nervous system feels safe can the individual begin to approach demands with curiosity instead of fear.

And when that shift happens, things that once felt impossible begin to feel… approachable.

Exploring Your Relationship with Demands

Whether you're a person who resonates with PDA traits or a loved one/supporter, these reflection prompts can help deepen your insight and cultivate self-awareness:

When do I notice the most resistance to demands?

Are there specific environments, relationships, or types of requests that feel especially triggering?How does my body respond when I feel pressured or obligated?

Do I shut down, get irritable, procrastinate, or distract myself?What stories do I tell myself when I avoid something I wanted to do?

(e.g., “I’m lazy,” “They’re going to hate me,” “I’ll never follow through.”)Can I recall an early experience where my autonomy was ignored or punished?

How might that be shaping my response to expectations today?What helps me feel safe enough to engage with a task?

Is it having choices, low-pressure language, co-regulation, flexibility, or something else?How do I typically respond to perceived rejection or failure?

Can I see how RSD may be fueling my avoidance?What would it look like to approach myself with compassion instead of criticism?

What would I say to a friend who was struggling in the same way?

Key Takeaways: Understanding PDA at Its Core

Pathological Demand Avoidance (PDA) is a nervous system-based response to perceived demands, often rooted in anxiety, trauma, and a strong need for autonomy.

PDA can manifest in subtle or overt ways, from procrastinating on texts to intense shutdowns over daily responsibilities.

It is frequently misunderstood or missed—especially in individuals who are high-masking, perfectionistic, or emotionally sensitive.

Rejection Sensitive Dysphoria (RSD) often amplifies PDA by increasing the emotional stakes around perceived failure, judgment, or relational disconnection.

Resistance to demands is not about willful avoidance—it is a protective response developed in the face of pressure, fear, or relational pain.

Effective support focuses on co-regulation, emotional safety, flexibility, and autonomy—not pressure, compliance, or rigid behavioral expectations.

Healing begins when we shift the question from “How do I make myself do this?” to “What would make this feel safe enough to try?”

Pathways to Wellness

〰️

Francesca Wehr, LCSW

〰️

Mental Health Counseling

〰️

Pathways to Wellness 〰️ Francesca Wehr, LCSW 〰️ Mental Health Counseling 〰️

Ready to Feel Less Stuck? Let’s Talk.

If you see yourself in these patterns—or love someone who struggles with demand avoidance—you’re not alone, and you don’t have to figure it out by yourself. I offer trauma-informed, neurodivergent-affirming therapy to help you untangle the cycle, build nervous system safety, and reconnect with your sense of agency.

Reach out today to schedule a consultation or ask questions about working together.