Understanding Grief: The "Ball in a Box" Analogy and Its Impact on Mental Health

What if grief doesn’t shrink—but life grows around it?

Grief is one of the most complex and emotionally consuming experiences we face. It can upend daily life, alter your sense of time, and leave you feeling like the world no longer makes sense. Some days you may feel completely overwhelmed; other days, you might wonder if you're grieving the “right way” at all.

The truth is, there’s no single roadmap. Grief is not linear, and it doesn’t follow a neat set of stages. It’s messy, cyclical, and deeply personal. And yet, despite its unpredictability, there are frameworks that can help us understand it a little more clearly.

One of the most widely recognized and relatable is the “Ball in a Box” analogy.

What Is Grief?

Grief is the internal process of responding to loss. It’s often associated with the death of a loved one, but grief also follows other types of loss: the end of a relationship, a significant life transition, a job loss, a chronic illness diagnosis, or any event that marks a before and after.

It can show up as sadness, but also as irritability, guilt, numbness, anxiety, forgetfulness, or exhaustion. It can impact your sleep, your ability to concentrate, or your sense of safety in the world.

No two grief experiences look the same—but many people find themselves asking the same question: Will it always feel this heavy?

The “Ball in a Box” Analogy

This analogy was first shared by a physician and later popularized by Lauren Herschel. It’s become a go-to tool for understanding how grief and emotional pain evolve over time.

Imagine a box with a pain button on one wall. Inside that box is a large ball—your grief. When the loss is fresh, the ball is huge. There’s almost no way to move the box without that ball pressing hard against the pain button. Nearly everything—memories, songs, silence, sudden reminders—sets it off.

Over time, the ball begins to shrink. It still hits the pain button, and the pain is still sharp—but it happens less often. As the ball gets smaller, it moves more freely in the box. You get longer stretches between painful collisions. More space opens up. You begin to function again, even laugh again.

This analogy helps normalize the experience of those sudden grief "spikes"—the ones that show up months or years later and feel as intense as day one. It’s not a regression. It’s just the ball hitting the button again. And that’s okay.

But not everyone experiences grief this way. And in my work, a conversation with a client helped me recognize a meaningful variation.

What If the Ball Doesn’t Shrink?

After sharing the analogy with a client who had lost a parent, she paused and said:

“That doesn’t feel quite right. My grief hasn’t gotten smaller. What’s changed is… me. My life. There’s more space around it.”

That observation stuck with me. Because for many people, the idea of grief “shrinking” doesn’t resonate. In fact, it can feel like pressure to move on or let go—when what they’re really doing is learning how to live with something that still matters deeply.

So here’s another way to look at it:

Maybe the ball stays the same size. But the box gets bigger.

You grow. Your life expands. You create more space around the grief—not by minimizing it, but by building something larger around it: relationships, moments of joy, new layers of meaning, new ways of being.

The pain still exists. But it’s no longer the only thing in the box.

The Emotional and Psychological Impact of Grief

Grief touches everything—emotions, thoughts, body, relationships. It’s not just “feeling sad.” It can include:

Anger or irritability

Anxiety, especially around safety or future loss

Guilt about surviving or about moments of happiness

Numbness or feeling emotionally disconnected

Brain fog or forgetfulness

Difficulty sleeping or eating

Grief can also interact with mental health conditions. Some people develop:

Depression, with persistent sadness, hopelessness, or loss of motivation

Generalized Anxiety, with heightened worry or panic

Trauma symptoms, especially after a sudden or violent loss

Prolonged Grief Disorder, where the grief becomes stuck and interferes significantly with functioning

These aren’t signs of weakness. They’re signs that grief is overwhelming the system—and that you may need more support.

What Healing Actually Looks Like

Healing doesn’t mean forgetting or reaching a tidy resolution. It means adjusting to a new reality. It’s not about shrinking the grief—it’s about becoming someone who can hold it with more capacity, more gentleness, and more room to live alongside it.

That might look like:

Having good days that don’t erase the pain

Laughing without guilt

Making space to talk about the person or situation you’ve lost

Feeling triggered and knowing it won’t last forever

Finding small joys and still carrying sorrow

Healing is about integration, not erasure.

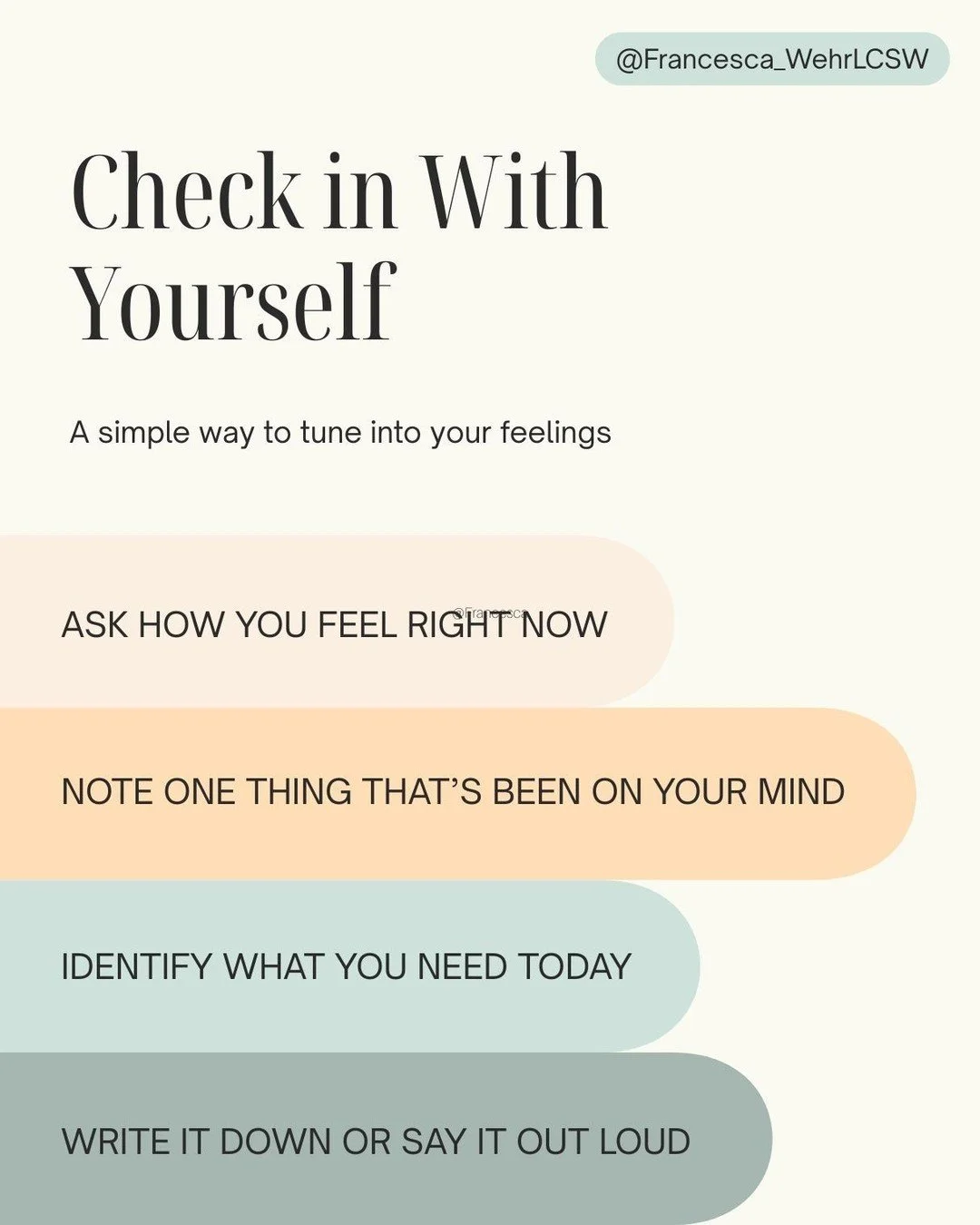

Coping Strategies That Support Growth

There’s no one-size-fits-all method for grieving, but here are strategies that help many people create a bigger box:

Talk about it. With a therapist, a trusted friend, or support group. Name the loss. Say their name. Let it exist.

Let the emotions come. You don’t have to be composed. You don’t have to “stay strong.”

Rituals matter. Whether it’s lighting a candle, writing a letter, or marking anniversaries, rituals help bring structure to what feels chaotic.

Take care of your body. Grief lives in the body. Move gently. Rest when you can. Nourish yourself.

Stay connected. Even if only in small doses, human connection buffers against the isolation of grief.

Mindfulness and grounding. Practices that anchor you to the present can help regulate the nervous system when grief flares up.

Give yourself permission to go slow. There’s no race. No fixed timeline.

When to Seek Professional Help

There’s no shame in needing support. If grief feels stuck, isolating, or overwhelming, therapy can provide structure, language, and space to process it.

You may want to seek help if:

You feel unable to function day-to-day

Your sleep, appetite, or energy have been disrupted for a long time

You feel numb, hopeless, or overwhelmed

You’re experiencing panic, trauma responses, or intrusive memories

You feel alone in your grief and want a space to explore it without pressure

Therapy doesn’t take the grief away—but it can help you carry it differently.

Final Thoughts: Grief Doesn’t Have to Shrink for You to Heal

The original “Ball in a Box” analogy helps explain why grief feels so sharp at first—and how it can become less constant over time. But for some, a more accurate image is this:

The grief remains. It stays the same size. But you grow around it.

With time, you expand. You adapt. You stretch your life to hold both sorrow and joy.

You don’t forget what mattered. You learn how to live with it.

And in that process, healing quietly takes shape—not by asking you to move on, but by allowing you to move forward.