Understanding the Tapestry of Trauma Responses: A Deeper Dive

Trauma Responses: A Tapestry of Survival and the Path to Integration

In the realm of mental health and healing, trauma is less a singular event than it is a fracture in the continuity of safety—an invisible rupture that severs the ordinary sense of predictability we rely on to function, connect, and thrive. To understand trauma is to understand a complex tapestry of adaptive responses—woven from the threads of past experiences, unmet needs, emotional defenses, and the subconscious ingenuity of survival.

Trauma does not exist solely in what happened, but in how what happened lives on within us. It alters our internal landscape, reshaping our nervous system’s thresholds for trust, risk, and emotion. What often gets mislabeled as maladaptive behavior, emotional instability, or personality quirks are, in fact, the residue of a nervous system that has had to adapt quickly, repeatedly, and—at times—desperately.

The Spectrum of Trauma Responses

Trauma responses are not one-size-fits-all. They are vast, diverse, and deeply contextual. Many are mischaracterized as pathology, yet they serve specific functions—namely, to prevent further pain, reclaim agency, or create a sense of safety in an unsafe world. Below is an exploration of the nuanced ways trauma can manifest:

Over-Sharing or “Trauma Dumping”

What may appear as an overwhelming or unsolicited disclosure of traumatic experiences is often a coping mechanism—a way of externalizing internal chaos in an attempt to regulate unbearable affect. The act of sharing may be compulsive, but it reflects an unmet need to be witnessed, validated, or understood. Psychologically, this can be an attempt to reclaim narrative control or to distance oneself from the internal burden of unprocessed memory.

Rather than shame this behavior, therapeutic work might explore: What are you hoping someone might finally hear? Whose comfort did you need when you were silent the first time?

Hyper-Independence

When trust has been repeatedly broken, vulnerability becomes dangerous. Hyper-independence is often a defensive posture—one that constructs self-sufficiency as armor. While it may project strength, underneath is often the implicit belief: No one is coming to help me. It is the learned conviction that dependency equals risk and that needing others is synonymous with being harmed.

Healing invites a redefinition of interdependence—not as weakness, but as relational strength built on consent and reciprocity.

People-Pleasing

People-pleasing is not simple politeness. It is often a trauma adaptation arising from environments where love was conditional, approval was inconsistent, or conflict was unsafe. This response internalizes the belief: My worth depends on meeting others’ expectations. It becomes a strategy for emotional survival—one that trades authenticity for acceptance, at the cost of self-erasure.

Therapy here involves boundary reconstruction, inner child healing, and the reclamation of one’s own needs as equally sacred.

Emotional Numbing and Detachment

Numbing is a form of psychic triage. When the intensity of emotion becomes overwhelming, the psyche may downregulate affect entirely. Individuals may report feeling disconnected from themselves, indifferent to formerly meaningful activities, or incapable of accessing a full emotional range. This is not apathy—it is protection.

Emotional numbing often coexists with profound longing. The therapeutic goal is not to “re-feel” everything at once but to restore emotional bandwidth with care and regulation.

Hypervigilance

Hypervigilance is a state of perpetual alertness rooted in the nervous system’s anticipation of danger. It is common among individuals who experienced environments marked by unpredictability, betrayal, or chronic threat. While it may masquerade as attentiveness or conscientiousness, it reflects a lack of felt safety. Sleep disturbances, anxiety, exaggerated startle responses, and somatic tension are often present.

Over time, this state of high alert becomes exhausting. The work is to help the nervous system relearn what safety feels like—not just intellectually, but somatically.

Dissociation

Dissociation serves as a psychological exit door when the body and mind can no longer tolerate presence. It can feel like watching one’s life from the outside, experiencing time loss, or becoming disconnected from one’s thoughts or physical body. It is both a fragmentation and a sanctuary.

Healing involves pacing. Gentle body awareness practices, trauma-informed mindfulness, and parts work can support reintegration without overwhelm.

Regression

Under duress, some individuals revert to earlier developmental behaviors—thumb-sucking, childlike language, increased dependency. This is the psyche’s effort to return to a perceived state of innocence or simplicity. These behaviors are not signs of immaturity; they are attempts to access internal resources from an earlier time when life may have felt more manageable.

Rather than interpreting regression as dysfunction, it can be honored as a signal: What part of you needs to feel held right now?

Somatic Symptoms

Trauma lives in the body. When psychological wounds remain unspoken or invalidated, the body may speak in symptoms—chronic pain, digestive distress, migraines, fatigue. These are not “all in your head.” They are embodied expressions of unresolved stress, grief, or fear.

Modalities such as EMDR, somatic experiencing, and polyvagal-informed therapy can facilitate dialogue between mind and body where words alone fall short.

Risk-Taking Behaviors

Substance use, reckless behavior, compulsive sex—these responses may serve multiple purposes: distraction, numbing, self-punishment, or the recreation of chaos in a controlled context. They often reflect a nervous system seeking intensity as a substitute for connection or a reenactment of trauma with the illusion of power.

Interventions must go beyond symptom control to address the underlying narrative: What are you trying to feel—or avoid feeling—when you take these risks?

Nervous System Literacy: The Biological Roots of Trauma Responses

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) governs our survival responses. Trauma dysregulates this system, often trapping individuals in sympathetic overdrive (fight/flight) or parasympathetic shutdown (freeze/fawn). In this state, the body and brain are no longer oriented toward growth—they are preoccupied with survival.

Fight/Flight: Heightened arousal, irritability, compulsive activity, anxiety.

Freeze: Numbing, disconnection, inability to act.

Fawn: Appeasement, chronic self-abandonment to maintain connection.

Understanding these responses as physiological—not moral—shifts the frame from blame to compassion. It also underscores the need for body-based healing strategies alongside talk therapy.

Reframing the Narrative: From Pathology to Adaptation

The common thread among all trauma responses is this: they worked. At some point, each strategy was the best available option. The problem is not that these responses exist—it’s that they often persist long after the danger has passed.

Healing involves acknowledging the brilliance of survival, while gently updating the nervous system’s story: We are not there anymore. We are here. And here, we are safe enough to choose differently.

Journaling and Creative Reflection: Your Tapestry

Imagine your trauma responses as part of a tapestry—a rich, intricate weaving of pain, resilience, creativity, and adaptation. This tapestry is not just the story of what happened to you; it’s the story of how you survived.

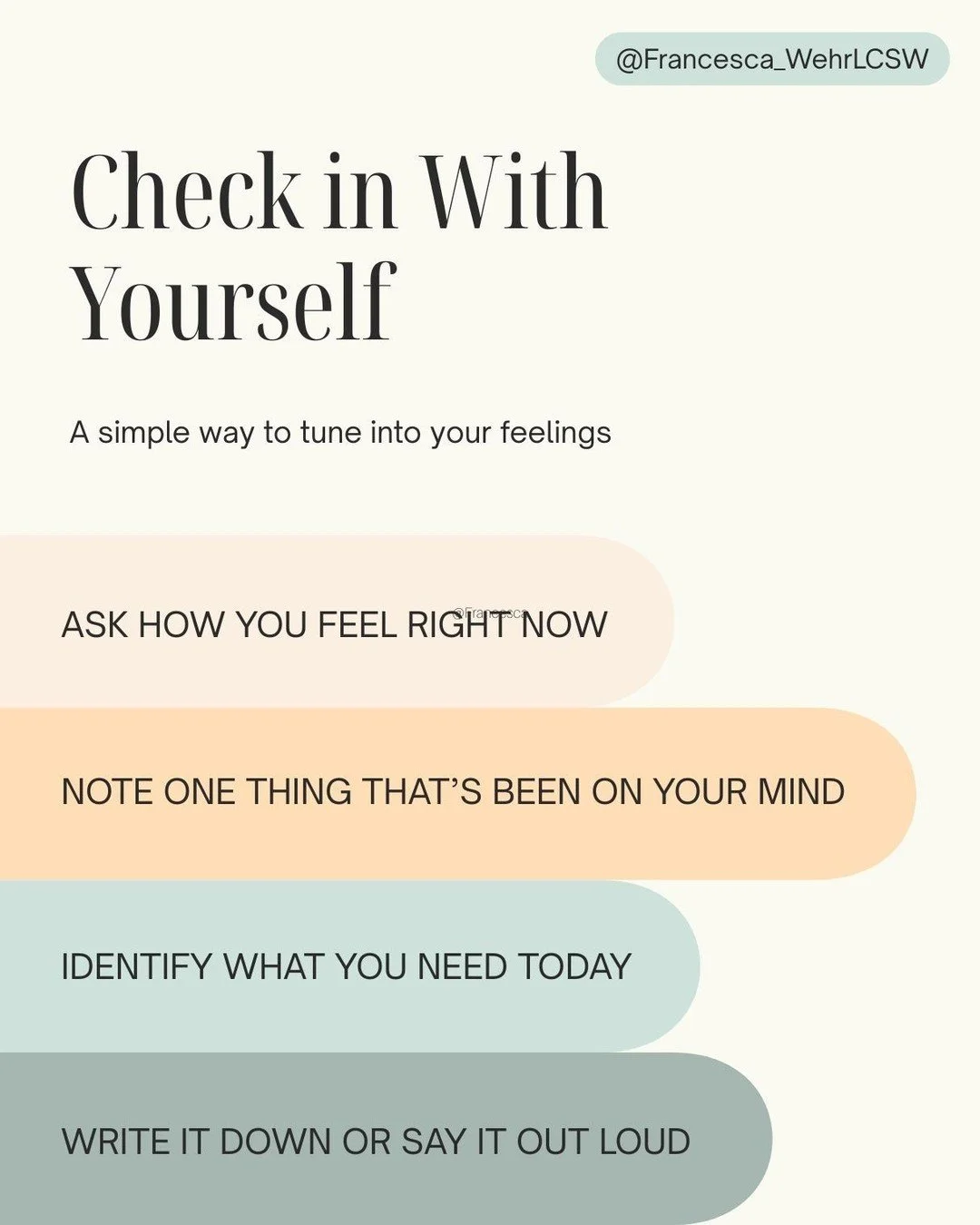

Reflective Prompts:

Which trauma responses resonate most deeply with your experience?

What unmet needs might those responses have been trying to meet?

How does it feel to recognize these responses as survival strategies rather than flaws?

What moments in your life represent bright threads—instances of clarity, connection, or agency?

If you were to begin weaving a new section of this tapestry, what colors, patterns, or symbols would it include?

Consider sketching, collaging, or journaling your tapestry. What does it teach you about the resilience you may have forgotten you had?

Final Thoughts: A New Thread of Compassion

To understand trauma is to move beyond diagnosis toward deep, embodied compassion. It is to honor survival without letting it dictate the entirety of one’s identity. Healing is not linear, nor is it neat—but it is possible. With safety, psychoeducation, and support, we can begin to untangle the knots, thread by thread, and weave a life that reflects not just our past, but our possibilities.